Revised December 2011.

Proportions, Leg-length Ratios, and Breed Standards:

Using the Vizsla and the German Shepherd Dog as Examples

In early 2003, there began an argument in the circles of Vizsla fanciers in the Vizsla Club of America, VCA. This Hungarian breed of dog is a moderately-sized and agile hunter well suited to “upland” field work (woods, broken fields, pastures). There are some who wanted the Standard reworded to aim at a dog with exactly as much depth of chest as “daylight” under the torso, and opponents who insist on retaining the ideal of slightly more proportion of the dog’s height being underneath the chest (although they use the elbow as a reference instead).

The Breed Standard of the SV (the club for GSDs, HQ’d in Germany) says: “The chest should be moderately broad, its underline as long as possible, and pronounced. The depth of chest should be about 45 % to 48 % of the dog’s height at the withers. The ribs should widen out and curve moderately. Barrel-shaped chests or slab-sided appearance are equally faulty.” This Standard is accepted by almost every country in the world, the U.S.’s AKC club (GSDCA) being a flagrant exception. You can find my translation on several websites, including SiriusDog. This is approximately the right proportion for almost all dogs of medium-to-large size and normal anatomy (i.e., excluding dwarf, toy, and giant breeds) that are similar to the ancestral type. If one aims for the space below the chest to be about 55% of the dog’s height, it will be as ideal as possible. The height as measured immediately behind the shoulder blade and the “stick” resting on the vertebrae there, allows the vertical portion of the wicket to pass along or immediately behind the “point” of the elbow (olecranon process), and the horizontal foot of the device to be on the ground immediately behind the paw, without interfering with its normal position/stance. Whether in the GSD, Vizsla, wolf, Saluki, or most ancestral-type breeds, these proportions suit the function of versatile hunters, herders, and other utilitarian dogs.

The measurement in the 2003 or proposed Vizsla Standard “proportions controversy” does not address a minor problem as well as the SV Standard does. In the Vizsla, “the elbow” is not defined as a specific point of reference. That is, where is “the elbow”? At the center of the humeral condyles? At the bottom, where the joint gives way to the radius and ulna? At the top of the olecranon process? (That is the best place because it is visible and definite.) A better description of where the judge’s eye and/or hand should be drawn is in the (German) GSD Standard: the underline of the chest between and immediately behind the elbow. There is no significant variation between evaluators if that is used as the dividing line between top and bottom “halves” of the dog’s outline and height. By the way, when I speak of leg length here, I mean to draw more attention to the lower leg, even though the upper arm will also be longer in moderately or very tall dogs.

Sighthounds are typically built with even a greater leg-length-to height ratio than the gundog, guardian, and herding breeds. Their more upright shoulders and croups serve them better for the double-suspension gallop in which they “fold up” and extend to a greater amount than other breeds do, and the more vertical foreassembly results in a little more space between the olecranon and the underline. The shorter the breed and the dog, the lower will be the leg-length-to-height ratio. Think of Toys, Cockers, Brittanys, and smaller dogs.

There are good, function-related reasons why history has given us these ratios. Breed Standards ideally are written to describe the existing breed, i.e., the best, most functional, most useful specimens. If (that might be a big “if”) the breed is represented by a population that does its job well, whether endurance trotting during herd control, or bounding over obstacles and broken-field running after game, etc., and if the Standard writers are knowledgeable about anatomy, the Standard might be written well. There are some that are abominable for one reason or another, and there are some (such as the SV’s) that are excellent, though not faultless. Complexity is not always beneficial—the Greyhound Standard is the soul of brevity, yet the breed has not suffered greatly from the artificiality of dog show guidelines for breeding. The biggest reasons for some Standards not rising to the good sense and usefulness include changes that originate from club members’ fancies more than in the dogs’ function. The best that a dog show judge or breeder can keep in mind is, “Does this dog look like it can do the job for which the breed was developed?”

Quoting from a document circulated by Vizsla Club of America members, “It should be noted that the change originally proposed by the VCA’s Board of Directors has been amended by the addition of the following proposed sentence: ‘Under no circumstance should the distance from the elbow to the ground be less than the distance from the elbow to the top of the withers.’ While this eliminates one of the concerns raised with respect to the original proposal, the essential objection remains that this proposal would allow a functionally incorrect dog that is too low on leg to be described as ideal.” It is obvious that opponents to the Standard change are afraid of letting the camel get his nose into the tent.

Now, there will not be any substantial damage to the Vizsla if the American club decides to call for a 50/50 ratio in height. But if you go in that direction, there will be many more cases of dogs with actually shorter legs than proscribed, and many of them will be awarded championships by judges who do not care enough about function, history, or club preferences. Look at what has happened to the American-lines GSD. Besides an extreme variation in type that is being rewarded with show wins, there is a big problem with too many being too short on leg (though this is even worse in the Alsatian type of GSD in the UK). In some cases, the observer is almost reminded of Basset Hounds. I believe much of that slide into incorrect proportions comes from an unfortunate misapplication of the concept of American independence, and a haughty, superior attitude toward the country-of-origin. In most cases, the originating country will have produced the more correct dog, and the reason for that is simple: it is there that function has formed the breed. In the cases of both the GSD and the Vizsla, and I daresay most other normal ancestral-type breeds, the leg-length ratio in the original examples (and hopefully in the written Standard) will be similar to that of the German GSD: approximately 55% of height below the underline at the elbow area.

Wording is important in any written Standard and in communications to club members and judges. The arguments regarding the VCA Standard unfortunately lack a little clarity in definitions. In the same paragraph in one very good document circulated among VCA members, the “Depth of Chest refers to the distance from the top of the withers to the elbow, the chest being understood to come down to the elbow as called for in the breed standard. Length of Leg refers to the distance from the elbow to the ground.” and “…measuring the length of leg below the chest and dividing it by the depth of chest. Assuming the keel of the chest to be level with the elbow, this ratio can also be expressed as a measure of the distance from elbow to ground divided by the distance from top of withers to elbow.” As I indicated, since the elbow joint of dogs of this size can be as much as 3 inches in its own depth, that quote does not give us precision. What we need is a reference point, not a reference area, if we intend to talk about percentages and measurements. The VCA should settle on definitions before continuing discussions, I think. Saying that the chest should ‘come down to the elbow” is not the same thing as saying “the keel of the chest” is level with a specific, anatomically-identifiable part of the elbow.

It has become customary in some registries for judges to appear to treat all breeds as having the same historical function. That is, they incorrectly give as much emphasis to outreaching gait in a Shiba, Italian Greyhound, or terrier as they do to a sheepherding breed whose ancestors’ job required endurance trotting. An APBT/AmStaff, a Chow Chow, or any of the bulldogs and mastinos were not modified for sheep herding and tending, but for fighting, and therefore the ability to get its feet under itself with strength and stability was more important than length of lower forearms or lower thighs (the latter popularly known as “rear angulation”). Otherwise the boar or bull would make short shrift of them.

Most hunting breeds of greater height than the Beagle have an intermediate function and structure between the terrier-schnauzer-pinscher types, the sheepdogs, and the sighthounds. They are not required to be as angulated in the rear as the all-day trotter, nor to be able to turn on as small a dime as the Shiba, nor have the low, square stance that keeps the fighting dog from being rolled over. Neither should they depart much from the ratios of chest depth to overall height that are required by the Standard for the very utilitarian and versatile GSD.

Yes, it is important to have accurate measurements if one is to keep the breed in question to its original or revised function description. One means of insuring that is to explicitly and unequivocally define terms and reference points, and one means of enforcing that is the breed survey. Periodically or else in the case of every dog passed for breeding rights, the dogs in almost every breed should be measured and the results recorded, later to be compared with performance results, taking into account the variable effect of attitude and “drive” as well. The SV requires each individual to have a performance title (such as a Schutzhund or IPO degree) and other prerequisites, and to be thoroughly “measured in” before eligibility to breed, or allowing any of its progeny to be registered as purebred. The Germans are great for keeping meticulous records, and breed surveys for such dogs as the GSD, Rottweiler, and many more are very valuable to the conscientious breeder. Those who do the measuring and certifying must pass rigorous tests as well. Once the dogs are admitted into that surveyed group, the judge can use visual comparison to segregate them according to more minor individual differences.

There exists the myth that “increasing the length of leg invariably results in a poorly angulated front.” Perhaps this misconception comes from the observation of sighthounds, who as a rule have concurrently both a relatively upright front and more space than other breeds between the chest underline and the “point of the elbow” (top of the olecranon). Those who have been fooled by this have perhaps not looked at the all-too-common, short-on-leg American GSD whose notoriously vertical foreassembly makes the legs appear to have been dropped from the ears with the help of a plumb line. Just look at the photos of GSDCA National Specialty class winners and see if you can find a singke dog with a forechest! The fact that many of the taller dogs, the ones with longer lower legs and the chest obviously above the point of the elbow, are sighthounds and thus more vertically constructed in front, is coincidental. Other breed types that include tall dogs have no such effect of size or height on front angulation.

Getting back to the gundog, and specifically the liver-colored Hungarian: Cliff Boggs, the author of The Vizsla said “the length of the front legs from the elbow should be about equal to the depth of the body (chest) at that point.” I believe he was referencing the most easily seen point on the elbow, the top of the olecranon. Actual measurements made by that author gave “ legginess ratios” ranging from 1.23 to 1.04 while not a single one of the dogs measured by the book’s author had 50/50 proportions. Boggs clarified the statement, saying, “…the legs were longer than the depth of the chest, which represents better proportioned Vizslas. If I had to choose a ratio it would probably be 1:1.14… I would not do it without adequate statistics. It is just my opinion from forty-plus years of breeding, training and competing with the breed.” There is nothing like actual, accurate measurements, something the Germans in the SV and elsewhere have been famous for. Many of their statistics over a century are mentioned in my Total GSD book, the book by Max von Stephanitz, and records in SV archives. The meticulous observer Curtis Brown said, “Although …longer-legged sporting dogs should be able to trot well for their build, in the field they are designed more for galloping than for trotting.” In this respect, most of the pointer, setter, and retriever breeds are intermediate between the tending/herding-specialist type like the GSD and the purely galloping breeds such as the Greyhound. Even the GSD with its modern job utility has more function in agile galloping and jumping than it had when it was selected 100 years ago from the tending dog that moved flocks from pasture to pasture, and watched out for predators.

Another matter of proportions that is being bandied about in the current controversy is that of humerus (upper arm) to scapula (shoulder blade). It is a common mistake for people to latch onto drawings from the 1890-1920 era, some of which predated radiographs. But still, these early fanciful artists had fingers, and apparently did not use them. The proportions and the locations of bones and joints are grossly misrepresented. Yet, here we are in the latter days of “the age of enlightenmen ”, with most people still believing those erroneous claims of how a dog is constructed inside! There are minor differences from one dog to the next, in lengths and ratios of scapula to upper arm, but as little as a centimeter can show up in the appearance in stance and movement, since each bone is only a relatively few inches long. In the herding dog more than in the terrier-pinscher type, an upper arm as long as possible is of great benefit. It gives more room for muscle attachment and therefore promotes endurance as well as length of stride, springiness for jumping, and cushioning for landing. Naturally, such benefits are also desirable in a hunting dog such as the Vizsla.

I think everyone, whether he relies only on archaic pictures or on fingers and field experience, will agree that the ideal foreassembly has a scapula and upper arm of approximately the same length, and that restriction of movement and efficiency results when the humerus is shorter, or when the angle between the two is extremely open. But one problem in describing or seeing the best shoulder is the inability to see radiographically, as Superman could in the comic books. Where the joint is, what the angle is, and where to draw the lines, even on a radiograph, are things not understood or agreed on by all. Even feeling the joint, or flexing the shoulder and arm to estimate the lengths, do not result in accurate measurements. Something like Rachel Page Elliott’s fluoroscopic moving pictures are needed. Or at least, successive radiographs of the front assembly of a dog in various degrees of flexion. The old sketches, often lifted from the 1920s book by von Stephanitz (the founder of the GSD breed) are very misleading regarding location and shape of bones, and location of the rotational axis in the joint. What you feel with fingers and see on the line drawing is not the center of that rotation! In my book, The Total German Shepherd Dog (www.hoflin.com), there is much more in the way of correct illustration and outlines of actual radiographs, and at least 17 of the 20 chapters are applicable to all breeds. Highly recommended for people with any other breed, too.

I have already said that the bones involved are not very long, and that a small change in length or ratio can have a noticeable effect on gait. Another thing to learn is that, while there are variations from one breed to another, and even within a breed between individuals, these variations are far less as you approach the midline and spinal column. That is, scapulas of different dogs are closer to being identical in length and layback than is the case with the upper arms. There are more variations in lower leg length and shape between breeds than there are in the upper arm. Likewise, the range of motion increases tremendously as one goes from spinal column to end of limbs. The scapula, as well as having less variation between dogs, has less variation in layback (angle, slope) than the upper arm has. Judges and breeders need to focus on the upper arm far, far more than on the scapula; in fact, we could just as well forget about the scapula altogether in most examples, and get along with our breeding programs just as well. Of course, there are going to be extreme examples, but these very upright shoulder blades will not be hard to spot. Such dogs, though, will likely have concomitant short and vertical upper arms. The combination makes the situation worse, but the major contribution to a “straight front” is in the upper arm.

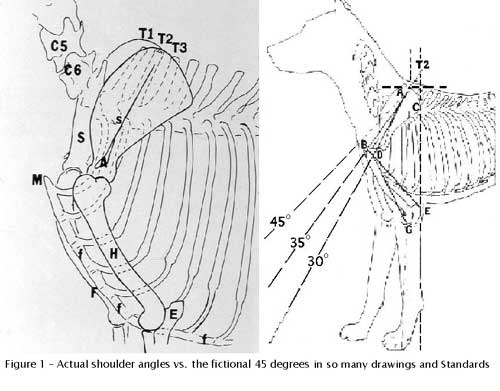

It must be remembered, when looking at some artists’ fanciful concepts of skeletal structure, that the 45-degree laybacks of upper arm and/or scapula are purely myths, promulgated by drawings that are not based on radiographs or even finger palpation. In my anatomy-and-gait seminars, I draw chalk lines on volunteered dogs, and have the audience feel where the articulation is and what the layback angles actually are. You cannot remain blind when you experience this. Figure 1 (from Rachel Paige Elliot) is an accurate representation of the proportions of a very good shoulder, drawn from radiographs of standing dogs of excellent structure.

Another very important matter of proportion is height-to-length. We shall leave out the poorly-worded and totally incorrect descriptions such as found in the Jack Russell breed standard and others, and look instead at the two breeds mainly discussed above. In a work presented by Vizsla and German Shorthaired Pointer fancier François-R. Bernier of Hull, Quebec, on the website , some excellent illustrations indicate that the best Vizsla or GSP length-to-height ratio is approximately 1.09 (0.91 height-to-length), in other words, about 9 high to 10 long. It may surprise AKC show-goers in the U.S. that this as well is close to the ideal for the GSD, according to its country of origin. That’s because more American-lines GSDs are closer to an 8-to-10 ratio or even some longer and lower than the international dog. The SV (WUSV and FCI) Standard for the German Shepherd Dog says, “The length of torso exceeds the measure of the withers height by about 10 – 17%.” That translates to between an 8.5-to-10 and a 9-to-10 ratio of height to length. The GSDCA wants a longer dog that is between 8-to-10 and 8.5-to-10, something I opposed when I was on the Board of Directors and afterwards. So the typical AKC dog is usually at one extreme (8:10) and the typical gundog is at the other extreme of this length/squareness range, 9:10. And the international GSD is in between, and a little closer to the working ideal of the pointing breeds. Figure 2 shows a typical American-style GSD with proportions that are not acceptable in the rest of the world (except part of Canada and a couple of pockets here and there amid the international dog in other countries).