The history and the Standard of the German Shepherd Dog are, and should be, intimately related to the “parent club” of the breed. That’s true with any breed. If one does not agree with that underlying principle of almost everything concerning the breed, then unity in the sport and identification as a breed will suffer. An English Springer Spaniel that does not look anything like the historic or the British dog perhaps should have “English” dropped from its name in countries where breed type has strayed significantly. The Australian Cattle Dog, if it starts looking like a Whippet after drifting in Transylvania, should not retain its name. If some of the Yanks or the Brits want a different breed than the internationally traditional GSD, let them call theirs the Alsatian or something else, rather than the German Shepherd. And fix this firmly in your mind as you read this article: Character should reflect that philosophy as much as physical appearance does.

Most dog people believe that any breed should reflect not only the purposes for which it was developed, but also should be the responsibility of the “home office”—that a breed should be held in trust by the “country of origin”. You cannot have all the passengers drive the bus at once; they must rely on the bus supplier to provide the driver.

This current discussion of the Standard was written in response to a request from Australia for an article about the use of the courage test at national (Sieger) shows. As a former English teacher I understand the reluctance to capitalize “Standard”, but as a poet and creative writer I’m going to continue exercising this license. The wording of a breed Standard is not the sum total of the breed, although many seem to operate on the principle that it is divinely inspired Scripture of private interpretation. Words are made by fallible men, and Standards can contain errors. Furthermore, a verbal description of a living creature is not the whole creature. The Standard is someone’s attempt to describe the ideal example of the particular breed. The breed Standard is a skeleton, and the flesh of understanding the breed can only be added by experience, intimate familiarity with the breed’s individuals, and an understanding of the history and function(s) of the breed.

One of the traditional reasons for existence of the GSD breed is the dog’s usefulness as a personal and property protector and as a working dog in such fields as military and police. To relegate the training in these areas of expertise to a handful of dogs owned by police and military forces would lead to the creation of a separate breed, a generic “police dog”, something that is happening already, with the loss of the GSD’s status in such occupations. The GSD is being supplanted by Malinois and Malinois crosses in such forces. No, it is up to the breeders and breed clubs to protect the breed, and this demands that we all encourage preservation of the protective nature of the animal through such things as Schutzhund training and testing.

As an aside of sorts, I relate again what to me was a surprising reaction to an address I made in 1991 to the gathering of the Australian GSD club (GSDCA) at their annual Main Breed Assessment/Show—a rough equivalent of a Sieger Show, but without courage testing. I had participated in a minor way in the judging the day before. I had summed up the philosophy of GSD experts and leaders since von Stephanitz when I said, “The Standard describes what the breed should be, the conformation show indicates what the breed appears to be, and the Schutzhund titles show what the dog really is.” At the time, I had no idea that the working and total-dog elements in the club were such pariahs in the eyes of the controlling officers and the ANKC (Australia’s all-breed monopoly). But my eyes were opened that evening, as I thought a riot was imminent. Cheers from the trainers and complaining sounds from the club managers and their adherents!

This protection-instinct testing idea, so taken for granted in Europe, turned out to be something that has been resisted in Australasia (the continent being the dog and New Zealand being the tail, some say). The Australian National Kennel Council (ANKC) has far too much power over breed clubs, a situation we see in the USA as well, with our monopolistic AKC behemoth. In Germany, the SV is still the de facto supreme guardian of the breed— at least, the breed is still mostly under the control of the leaders, breeders and trainers who are members of the SV. In the UK, the USA, and Downunder, it’s a different picture.

On a practical basis, as I was reminded by an Australian publisher, “[Our] people cannot tell the ANKC to go away, or else they could not show any of these dogs in the regular conformation ring (as opposed to the Main Breeds ring); but it is a hot potato indeed.” Agreed, it is a daunting challenge and probably it is more nearly impossible, given the history of government control over a greater portion of individual’s lives in the British/Australasian more socialist culture than is found in the cowboy-culture USA. But what really should be done, if and when the few clubs that make up the backbone of the national kennel organizations decide to flex their muscles, is a demand for a longer leash, for more self-government. OK, so it is unlikely to happen in our lifetimes, but that does not detract from the righteousness of the concept.

The sport and qualification test that was called Schutzhund (translation: protection dog) has been renamed as a result of forming the World Union of GSD Clubs (WUSV) in order to represent the sport instead of appearing as a one-country (Germany) club called the Shaferhund Verein. The tests and titles will probably continue to be referred to by diehard old-timers as Schutzhund, but the official designation of the title is now IP or IPO (International Protection Organization). Schutzhund seemed to be a dirty word among many British and Australasian politicians, and it has even corrupted the thinking of iconoclastic breeders in such few areas of the world as those. But it had early become an essential part of the breed, defining the nature and character of the GSD as first of all a working dog was clearly spelled out by the founders, especially Max von Stephanitz. His definition of “working” was not limited to sheep herding, or guiding the blind! As a military man, he strongly believed in preserving the traits useful to military and police, but in every GSD, not just those working in those jobs. This is why the SV, the Schäferhund Verein, uses the sport of Schutzhund (now for reasons of political pressure called Vielseitigkeitsprüfung or VPG, “many-faceted test”) as a proof (Prüfung) of traditional character.

Taken for granted in almost all WUSV-member GSD clubs worldwide, and with similar tests in other breeds, the courage test that makes up about a third of the activities at the annual BSZS (Bundessieger Zuchtschau, or German Sieger Show) is treated differently according to country. Some few countries’ national breed clubs require the test at every major specialty show, but most do so only at their “annual national” show. And in some countries, clubs somehow manage to hang onto WUSV membership despite the facts that they ignore the mandated test or are forbidden to use it, by their nation’s government-run or government-pressured all-breed club.

Before we get into the description of how the courage test is performed and why it is needed, you should know something about “where I’m coming from.” My first GSD in 1947, in New Jersey, was an “immigrant” or the son of an import — unfortunately, all records were lost. I had many GSDs since then, both “German” and “AKC” lines, mostly the former. I have owned offspring of Gin Lierberg, Uran Wildsteigerland, Lance of Fran-Jo, Timo Berrekasten, grandsons of Cello Romerau, Bernd Kallengarten, and many more. I have trained innumerable dogs for myself and others in AKC-type obedience as well as Schutzhund (all of them so-called “show-dogs”), and am a member of the somewhat elite UScA “SchH-3 Club.” As a professional handler I have put championships and high V-ratings on many dogs. I have had hundreds of puppies, and many years experience as a canine behaviorist and consultant. I have judged and lectured in some 30 countries and have seen the gamut of training and club requirements for shows and breeding. I am the author of “The Total German Shepherd Dog” as well as several other books. Not bragging—just saying how blessed I’ve been in this sport. Sometimes one has to re-establish one’s credentials, because the nature of the dog sport is that there are perpetually novices added to its ranks who don’t know us old-timers, and there are also “perpetual novices” who’ve been around a long time but still “don’t get it”.

With this background, and a long history of conducting annual tours of Europe centered on the Sieger Show, and including visits to trainers and training clubs, I don’t think there are many still active who have as much exposure to the breed in all its facets. I believe firmly that von Stephanitz’ dream of the total dog should continue to be respected. My ideal (and I’ve owned several examples) is the “golden middle” that can make me happy in both anatomy and character, both gait and performance.

And so, in the decades that I led tours to Germany and the Sieger Show, I emphasized to my groups the importance of seeing for themselves the character demonstrated by the conformation competitors. Namely, the preliminary and prerequisite courage test being held on the first day, Friday. Those that pass can then go to the next part of the grounds for the “standing exam” and gaiting, with the detailed written (dictated by the judge) critiques and a preliminary ranking assigned at that time. Those that do not meet the minimum performance standards (the Friday “bitework”) go back to their dog trailers and sit out the rest of the show weekend, then home for better training or for sale to a country like India, Australia, or another where the test is not required, or where it is thought it might be easier to pass it. There aren’t many of those anymore.

The excerpt used at Sieger Shows is an exercise that is supposed to test both character/courage and obedience. What more can you want from a dog whose breed was built on these foundation pillars? How can anyone with good sense and a respect for the historical function of the breed expect to “breed true” without such limitations and requirements?

You readers who want to know more about the courage test—commonly referred to as “the bitework”—used at such major conformation shows in most of the world may be interested in how it is performed. In those countries, it is a prerequisite for competition in their Sieger Show adult ring (over 2 years old), to weed out the worst-character dogs before they are allowed into the conformation judging. The German model is followed, this being excerpts from the two protection exercises of the IP or Schutzhund (VPG)-1 Phase C (protection) routine commonly known as “the attack out of the blind”, and “the long attack”. It is a highly stylized simulation of “street” situations, the first exercise being when a person and dog walking along minding their own business are suddenly attacked by someone jumping out at them from a hidden place. The dog is supposed to protect his handler by interposing himself between owner and attacker, and stopping “the bad guy” by biting him (on the arm) until the attacker stops fighting. In the second exercise, the “bad guy” trespasses, refuses to leave, and makes a threat by charging at the team from the far end of the “property”; the dog is released and rushes downfield to apprehend the intruder. At all times, the dog is expected to be under the voice control of his handler, and must stop and release his bite when the fighting stops and (if necessary) he is commanded to “out”. He must also keep heeling in Part 1 until the threat is obvious—only after the perpetrator appears and charges.

In countries where the test is not used, we find an even greater trend toward increasing the gulf between the working-sports portion of the fancy and the show-only community. This splitting of the breed into two breeds, and the fanciers into even more widely divided camps than is already evident, is a natural (though detrimental) effect of suppressing this very important test, or of performance (bitework) judges not being demanding enough of the courage shown.

At the Sieger Show qualification test, there is a little bit more leniency than in a regular Schutzhund trial (oops—excuse me, the VPG), with the judges a little more forgiving in regard to correct heeling, number of times the “Out!” command is allowed, and how close the handler gets to the dog before yelling at it, but basically, the worst passing performances resemble the work of the lowest-scoring dogs in a regular Schutzhund trial. It should be said somewhere that there are different terms for this SchH title, now officially known as IP or IPO (think of it as International Protection Organization), but it will be a long time before trainers lose the traditional name of the sport. The first half of the test is the “attack (on handler) from the blind”, and the second part is the “long attack”. Together, these exercises are known as “the courage test” and such minimum evidence of this protection ability is required at the Sieger Shows of most nations.

Come and watch with us now, as a team of handler and dog do the exercises at such a show. First, a few teams are lined up outside the large field, which is usually about the size of half or three-quarters of a soccer field, waiting their turns. As the preceding team exits via a different gate, and the judge announces their status as “pass” or “fail” and (if they pass) whether the dog was “pronounced” (ausgeprägt) or just barely “present” (vorhanden), the next team walks to the starting point. The judge gives an indication that he is ready for them to begin, and the handler heels his dog to the next marker, at least five paces from the first blind that is a bit to one side, stops with dog sitting, and removes the leash. There is a helper (“bad guy”) hiding in the blind, which of course the dog fully knows, but is supposed to act surprised when the helper pops out in a very threatening attack on the handler.

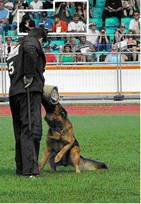

The team, upon a nod or gesture from the judge, starts heeling off-lead in the general direction of the blind. Most dogs that properly continue heeling show considerable, but self-controlled, desire to leave when the opportunity (threat) appears; in fact, most will eagerly crouch with lowered head as they heel, because by thus lowering the center of gravity, they can spring forward with more power and initial speed when that happens. This has occasionally been mistaken by Australians and others who have no experience in the sport, or people who do not understand dog psychology, as fear or intimidation. It is not—it is the dog’s self-imposed off-lead restraint. In an accompanying photo, you can see my friend Andrew Masia with his Leri Unesco doing just that, on the way to the off-leash marker. Andrew is an experienced trainer, and does not need the leash even when it is allowed. I trained and titled a bitch for him, once, when he was too busy working.

As they get near, the attacker runs out, waving his stick (and usually being noisy). The dog immediately, without any command being needed from the handler, charges at the bad guy to intercept him and thereby protect his master. The bite on the sleeve should be immediate and convincing, and when the struggle ends, the dog is to release, with no more than 3 commands allowed (the dog’s name is considered a separate command). After the dog “outs” (releases), the handler is permitted to walk up to them and retrieve (heel off with) his dog. He heels to the far end of the field while helper #1 disappears.

When the team gets to the marker at the end, they turn and face the originating part of the exercises. From another far part of the field, helper #2 trots along, while the handler shouts at him to get off his property. The “bad guy” turns toward the dog-handler team and starts running fast and furiously, again with threatening shouts and stick-waving. The handler releases his seated, eager dog, the dog tears down the field and flies through the air at the end, to hit the helper and latch onto the sleeve. The good helper knows how to catch the dog by “giving”, the way a baseball player catches a fast pitch so he does not have a hard impact. The most applause comes when a hard-hitting dog is caught high and swung around in the air to be set down relatively gently on the ground behind the helper. That shows really pronounced drive and enjoyment of the work.

Again, the struggle stops, the dog releases with (usually) or without command. I like to train my dogs to “out” on their own when the fight stops, without a command from me. Some handlers have to scream at the top of their lungs, hoping the dog remembers how to count up to three and then obey. Then the judge allows the handler to approach the helper and retrieve his dog. In the courage test, there are many irregularities or straying from perfection that would cost the Schutzhund trial competitor several points, but here it is just pass or fail. If the work is not convincing, if the dog is weak or reluctant, he may get a “vorhanden”, meaning he can only get an SG (very good) in the conformation show, not a V (excellent).

After a German Sieger Show tour that I led (an annual event for me) a professional photographer gave me permission to use some of his excellent stadium shots. Credit: Franck Haymann, www.aniwa.com. Very incidentally, part of my tour group was in the background in the stadium in many of them. In one picture, I’ve outlined in white where we were sitting; the dog is just on the verge of letting go as the struggle has just stopped. Handler 1045 shows the 2004 V-1 Karat’s Ulk doing the after-struggle guard from the down position, which is useful to teach dogs that don’t really want to out and still remain so close to the tempting sleeve. Ulk was pulled before conformation judging in order to give another Karat’s dog a chance at the VA rating, a very unwise ploy, since the second dog did not get higher than V-1 anyway, and Ulk would almost certainly have been VA if only they had bothered to get a German breed survey on his dam. Some folks must have been kicking themselves in their rear-ends all the way home after that show! Number 1068, Torro Barenwald, is shown in a correct, attentive guarding mode while the handler comes to pick him up.

The picture below with the helper wearing a number 3 and doing what looks like a dance routine features Solo v Team-Fiemereck. The next picture: there are always a few working-lines dogs that compete in the Sieger Show. This one is resting in the vendor area just outside the stadium. Often, these dogs bred strictly for working competitions place far back in the pack… around 110th place or further. That’s because they are not as highly selected for the proportions, front angulation, long croups, etc. which show-line breeders are always trying to perfect. Most are there to show off (their routines are usually head-and-shoulders above those of the show dogs that get far less practice sharpening their protection skills) or a few trying to place high enough to earn points toward the Universal Sieger title. This is an honor given to high-scoring dogs at the annual German and international Schutzhund prüfung trials, who also do well in the breed ring. In 2005, the judge of the males decided that every dog competing was worthy of a V (excellent) rating, and gave no SG or lower ratings. Of course, that included only those that qualified in the preliminary courage test.

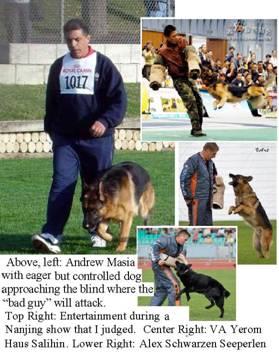

In the montage below, a working police-department dog in Nanjing, China in 2004 is properly and safely caught by a military helper (the “bad guy”) and is being set down. This was during a half-time break in my breed judging. You can see that there is very definitely a practical aspect and history to the courage test as it is carried out in a similar though more formalized manner than in real-life police or military situations. Yerom uses “in your face” intimidation. Alex demonstrates perfection in the protection routine.

In the very few places where courage is not tested, nor thought to be a requirement for a breedable GSD, this very practical aspect of breed selection (suitability for service in police, military, or personal protection) is kept at arm’s length by the people in charge of the show-line dogs. In Australia and its smaller cousin New Zealand, the officials of the GSD clubs are afraid of government repression and the threat of mandatory neutering, as had been the law not that many years ago when there was a breed ban on the GSD. They are ruled by the ANKC (Australian National Kennel Council), a quasi-governmental body heavily controlled by national politicians. The State politicians also get into the act, adding their own repressive anti-dog, anti-sport laws on a more local level. Many feel it is a case of the tail wagging the dog, and instead of the government being the servant of a free people, it is the master instead, able to dictate more severe limits on individual liberties than in some other countries. But as long as the citizens vote for such “governors”, they deserve what they get. Europe has long been sliding in the direction of less freedom for dog owners, and America is also slipping in that direction, though still far behind.

What is the purpose of the courage test in today’s societies? If you acknowledge that character is historically the primary feature of the German Shepherd Dog, the answer is obvious: it is to provide a proofing tool (that’s what the word prüfung means) to weed out the weakest temperaments and least useful individuals, and by such genetic population pressure, maintain the true German Shepherd Dog. We don’t expect every GSD to be used in police or military work, but neither should it degenerate into a foo-foo breed and lose its identity. Even before Europe’s growth of cities, decline in wolf and other predators, and less need for sheep herding, von Stephanitz established the breed as the preeminent guard and protection dog for families as well as for all manner of civil and official work, from customs and border patrol to searching for lost children or escaped criminals. History has shown that degeneration in such working character follows the lack of genetic selection pressure for the necessary traits. The courage test is primarily an exercise in obedience, with willingness and ability to defend the owner. In fact, the whole Schutzhund routine is more an obedience test and demonstration than a show of biting or fighting.

What is the future of “protection as selection”? Mostly downhill, thanks to non-dog-owners being elected to political office. But, in the USA there is a movement called “MyDogVotes” (no spaces between words, if you are doing a Google search) with citizens of all political stripes uniting to campaign against politicians who pass laws that are detrimental to the full enjoyment of dog ownership, including the highly rewarding and satisfying sports represented by Schutzhund. The anti-dog forces of PETA and HSUS are well financed by air-head celebrities with more dollars than sense, and it will be a long, bitter battle. In Europe, Australasia, and individual communities in the U.S. and Europe, there are breed-specific laws written by idiots who don’t understand the first thing about dogs, human nature, or logic.

National and State laws (and lawmakers) must be traded in for better ones. As one publisher friend from the Land of Oz told me, “Our people cannot tell the ANKC to go away, or they would not be allowed to show any of these dogs in the regular conformation shows. We believe it is very important that top-quality GSDs also appear in the [all-breed shows] whenever we can tempt their owners to enter them. Otherwise the divide [between show and working/sport dogs] becomes even wider. Not many of them bother of course, but those that do are much valued and give us an idea of where the breed stands—interestingly enough, many of them do enjoy the ‘ordinary’ shows once they try them.” This was in response to my partly tongue-in-cheek suggestion that “Your GSD folks should just tell the ANKC to go away, and join the WUSV instead (whole-heartedly).” Right now, the GSDCA in Australia is resisting being a member in more than just the name; in effect, they are resisting the requirements of performance (proof of character), which in the majority of countries are inseparable from those of structure.

In England, a very interesting development has been unfolding. One of the three major GSD clubs in the U.K., the GSD League, is a WUSV member. But it has been in a similar position as Australasia until now, bowing to The Kennel Club in outlawing Schutzhund activities anywhere near its name. For a while, management of GSDL worked out some sort of agreement with the BSA (British Schutzhund Association). If anything comes of that, it indeed would be a hopeful sign. Another problem is that there is still the BAGSD (British Assoc. of GSDs) club that has been a rival organization and has close ties with The KC. And of course, there is the slowly-dying “breed” of dog owners known as the Alsatian fanciers, who still have something of a following.

Regardless of what happens in the Queen’s flower gardens up close or her back yard down-under, the rest of the world is staying the course, using the Schutzhund trials (even though renamed IP or VPG) and the shortened courage tests as selection tools to keep the breed on the right track as much as possible, given the wide variety of interests in the game.

A fall-out from the intentional splitting of the fancy, sport, and breed that some national kennel clubs (and their subservient national GSD etc. clubs) are promoting by their opposition to the courage test and the Schutzhund sport, is the alienation of those who breed for the sports dog. The “working-lines GSD” is what I mean. This arms-length attitude results in dogs that are bred solely for trial scores, so breed type suffers. Some look like Malinois, some like Dutch Shepherds, some have poor toplines, and most have poor angulation (though they may make up for that in endurance herding/trotting with high “drive”). Both wings of the breed fancy need to make peace and concessions, and strive for a reunited breed. We had that in the USA, even halfway through the 1960s, and it is not impossible to get back to a single breed, though variable within reasonable limits. The publisher mentioned above also said, “We believe it is very important that top quality [working-line] GSDs also appear in the regular conformation classes whenever we can tempt them to do so. Otherwise the divide becomes even wider. Not many of them bother, of course, but those that do are much valued to give us an idea of where the breed stands.” And, I add, valuable for the sake of genetic diversity, a subject in itself.

But it is equally important that the show-only folks keep an open mind and try to understand the history and purposes of the breed, and work toward the day when they can join the world community of GSDs, including the performance of VPG trials and required IP titles for breeding rights, for the more respectable and breed-worthy reproducers. I hope I live long enough to see all GSD clubs in Australasia, the UK, and those few other hold-out countries join the WUSV and conform to the international standards of the breed, which must include (and test for) proper character.