Lodi Police Officer Dee Dee Dutra said goodbye to her partner for the final time last week.

I called to ask her for an interview, but the wounds were still too raw. A week after it happened, she couldn’t speak about him without tears seeping into her voice.

I would have asked her how it felt, but I already knew.

I wasn’t there when Dutra said goodbye to her beloved friend

and partner. I wasn’t there when any of the other canine

officers cradled their dogs, feeling the life go out of them,

whether from injury or disease, when they had to say that last

goodbye, but I know, because there is a universal bond that ties

all dog handlers together, and I have a need to let you know for

all of us that it isn’t “just a dog.”

I wasn’t there when any of the other canine

officers cradled their dogs, feeling the life go out of them,

whether from injury or disease, when they had to say that last

goodbye, but I know, because there is a universal bond that ties

all dog handlers together, and I have a need to let you know for

all of us that it isn’t “just a dog.”

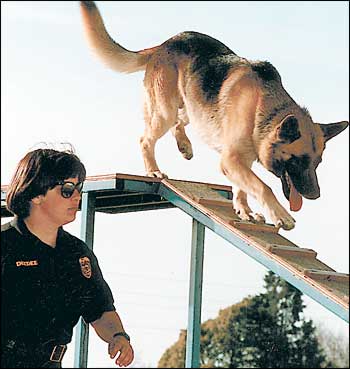

For Dee Dee, it was Alex, a German shepherd dog she got when he was about 2 years old. She loaded him in her car and took him home and at first thought she had purchased a Tasmanian devil.

He was a high-maintenance dog, and serious.

For me, it was Bolo. An officer with a Bay Area police department, I drove all the way to the Los Angeles airport to get him.

The porters wheeled out the cart with several plastic carriers on board. There were four or five dogs there, but I knew right away which one was mine. A handsome black and red shepherd, he was intense and focused, and ready to go to work — and I was a novice handler.

He nailed me — all the way through my right hand a month after I had him, and he was right to do it. I learned quickly what it meant to establish order between us, and for the first half year, the scale was tipped in his favor.

We had issues. We worked them out — because he was the searchingest dog you ever saw. He could find a shell casing in a half-acre patch of ivy, or a stub of a marijuana cigarette the size of your pinky nail in a shirt pocket in the closed trunk of a Cadillac. He could find a felon hiding on the roof of a four-story building by catching and working the scent as it wafted down and drifted against the walls.

He found a loaded gun that shooters had thrown from a car in a residential neighborhood. A little flip-top Beretta, it looked like a toy, and Bolo found it before the kids playing there could get to it.

He took a Buck knife in his neck one time, capturing a crazy man who had already stabbed two people. He took it, came off briefly, gushing red, and went right back, taking the man to the ground allowing me to handcuff him before cover arrived. When it did, I shoved the suspect in the sergeant’s car and took my bleeding dog to the vet with lights and sirens.

He survived. He went back to work. You couldn’t keep him from working.

He could and did protect me and other officers in bar fights and riots, and could and did go from a knock-down, drag-out fight where my finger was broken to a school demo with 100 third-graders tugging at his ears.

But I lost him, just shy of 10 years old, to a cruel disease — degenerative myelopathy. The same thing took Dee Dee’s Alex.

It is too difficult to describe to someone for whom a dog has never been more than a “pet.” Those people, well meaning, intending to be kind, say things like, “ Are you going to get a new puppy then?”

The less thoughtful look askance and say, “It was just a dog.”

When my sister’s son lay in the hospital with a life-threatening head injury, the nurse asked her if she had other children, as though that would ease the loss of this one.

A dog is not a child, but a working partner is more than a pet in ways “civilians” cannot imagine.

I lost him when his body wouldn’t listen any more. At least not his rear quarters. The myelopathy had eaten away at the sheathing on the spinal nerves, and while it didn’t hurt, not like stick-hits, or knife wounds, or broken bones, it was devastating — because his legs would not respond. They wouldn’t get him up off the floor, and when he did get up, with help he resented, they’d give out on him if he made a corner at faster than a walk. He’d slip and go down, vulnerable.

You tend to him gently now, careful not to insult his dignity.

His body let him down. The nerves lost communication, and would not tell him when he needed to relieve himself, so there was the inevitable “accident” — the kind that hasn’t happened since he was a pup. He has been fastidious about the house all his life, and now this. You learn how to express his bladder for him, to minimize those “accidents,” and arrange a towel sling to help him walk outside.

You try to make up exercises for him to keep his mind busy, because the disease is wicked. It allows the mind to stay sharp while the body disintegrates. Cruelly, it keeps him apprised of how bad things are, and you wonder when will be the time to say goodbye. How will you know? How do you presume to end his life before it’s time?

Your friends who have been there say, “He’ll let you know. He’ll tell you.”

And you hope they are right.

One morning, you go to him to perform the rituals of caring for him, and he doesn’t even try to get up to greet you. He only casts his eyes up, and looks at you, his chin still on the blanket where he spends his life now, and as clearly as if a word-balloon had appeared over his head, he says, “I need to go now. It’s time.”

He lost weight. He wouldn’t eat lying down. He had his standards and his dignity. A dog who cleared a 6-foot wall like it was a speed bump, who hit an arm hard enough to spin a 180-pound suspect and land him on his backside doesn’t lie down and lap at a saucer like a whelp or an invalid. He’d push to stand, and grit himself to balance on his useless legs so he could eat upright. He deserved that much.

You call the vet.

Your hand is shaking as you dial, and your voice is just a tremor, but you say the words. She listens. She knew the time was coming, and she is kind. “I’ll be over this afternoon.”

So you get ready.

You sit cross-legged on the floor now, stroking his head in your lap, telling him how the sentence will be over soon. How he’ll run and play and get the bad guys again in a place with evergreen grass, flowing streams, where tennis balls grow on shade trees, where bodies are forever young and there is no pain, where legs never fold underneath you or refuse to push you up from the floor.

You give him anything he wants to eat, if only he will eat. Some pepperoni? Peanut butter? It’s your birthday, buddy. Have a party. But there’s no pleasure in it. He licks at your finger, and looks up through the tops of his eyebrows, taking the morsel just to be polite.

Euthanasia solution burns a little, we are told. Don’t know how they’d know that. Don’t want to know, but just in case, you ask the vet to give a cocktail of ace-torbutol, a woozy tranquilizer to drift him off.

“I’m tired,” he says. “I need to go now.”

And you graze your palm over the rough velvet of his graying muzzle, and fold yourself in half to cover his head with your body as you sob. You cup his elbow and hold one foreleg out for your vet so she can slip the needle in, a sleepy cocktail to relax him so he’ll just slip away, and never feel it.

He’s still warm, and now his breath comes slowly, slowly. The trusting head grows heavier in your lap, and you don’t want to know which breath was the last, but there comes a time when you stop sobbing, and you know his heart has stopped beating.

Goodbye, my friend. My partner. There will never be another one like you. My life is the better for having known you and a little piece of it is missing now, and gone with you.