Revised December 2011.

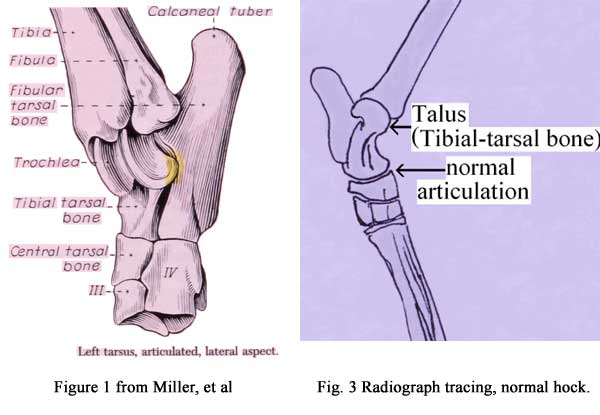

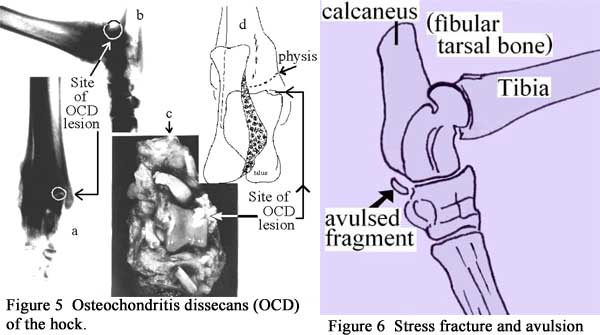

Osteochondrosis is a term applied to a number of similar disorders of the joints where bone (osteo) and cartilage (chondro) are involved. If they are inflamed we use the term osteochondritis. It is now a fairly common diagnosis in young limping dogs, the defects being found in one or more of those joints I named above. The hock joint is what corresponds to our ankle and first short bones in the foot, though the dog does not walk on the heel as we do. In the hock, the large bone of the lower thigh (tibia) rests mainly on the tibial tarsal bone, also known as the talus. The common specific expression of osteochondrosis in the hock is OCD (osteochondritis dissecans), which means, as it does in the shoulder and the elbow, a small piece of cartilage or bone has come loose in the joint of a young dog and is causing irritation and inflammation.

INCIDENCE OF OCD

Sweden’s Dr. S.E. Olsson reported on 51 dogs with hock ailments, 48 of which had a diagnosis of OCD of the hock, and the other 3 having osteoarthritis in the joint but no real sign of OCD. In all but one of the 48, the site of this osteochondrosis defect was associated with the rear part of the medial (toward the middle) ridge of this bone. Labrador Retrievers made up 23 of these dogs in Olsson’s 1984 group, with 10 Rottweilers, 6 Golden Retrievers, and smaller numbers of Beagle, Newfoundland, Schnauzer, GSD, Bouvier, and Welsh Springer also being included. Ten had lesions in both hocks. About half the flaps or mice were all cartilage, and 25% each were bone or both, the bone sometimes being formed by ossification rather than being pulled off. As in OCD of the other joints, this one begins with a defect in cartilage rather than a fissure in bone. In conversations with radiologists at Auburn University, I was told that they see tibial-tarsal OCD most predominantly in Rottweilers, a breed they also connect frequently with OCD of the humeral head and even panosteitis. In Australia, OCD of the hock is also seen in Bull Terriers.

In a later study of 89 dogs, Olsson concluded that “osteochondrosis of the hock does not show the same preponderance for the male sex” as seen in other joints. He surmised that this difference was connected with the fact that hock lesions are much more associated with a history of trauma. Heritability, therefore, may be lower for this ailment than for others. However, before you get confused between heritability and inheritance, you may want to read my new book on orthopedic disorders, unfortunately not yet in print as of the time of this article’s publication. For now, suffice it to say that they are not the same: heritability is a description of how environment can influence the expression of genes, and inheritance refers to the actual chemical structures we call genes being replicated and passed along in the formation of sperm and egg cells.

TREATMENT

Prompt surgical treatment is as much recommended in the hock as it is in the elbow. If surgery is delayed until severe DJD has started, permanent lameness is very likely even after surgery to remove calcium deposits or particles. Even if diagnosed early, a few cases will have a poor prognosis for recovery and freedom from limping and DJD.

GENETICS

Mason and Lavelle in 1979 found a familial characteristic in Australian Cattle Dogs. (Remember the early historical connection between this breed and the Shiba through the southern Asia Dingo.) A year later they and a couple more colleagues studied 68 dogs, half of which were Labrador Retrievers, bred by the National (Australian) Guide Dogs Association. When the pedigrees of the Labs were analyzed, it was discovered that most of them went back to one foundation bitch, and that the odds of any of these dogs developing osteochondrosis were greatly increased if both parents had that bitch in their pedigrees.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS ON OCD OF THE HOCKS

In the 1970s, Olsson reported a number of observations which were presented in the following 2 paragraphs, copied from his contribution to my 1981 HD book (that small edition is out of print now and supplanted by the new “Canine Orthopedics” book): “OCD of the hock may not be as common in your breed as in Labs, Rotts, and Goldens, but it is found in individuals of many breeds and it is wise to give attention to its possibility in cases of slight to severe lameness in the hind legs of young dogs. The clinical signs usually begin at 4 to 5 months and are usually very vague. The lesion is more often unilateral than OCD in other joints. The most typical findings are a slightly shorter step than normal on the affected leg and pain on extension and flexion of the hock. Rather early, the range of flexion is decreased. In some dogs there is obvious joint effusion (swelling). As in OCD of other joints, the radiographic examination (X-rays) provides the diagnosis. The lesion is located to the medial ridge of the talus and is best demonstrated as a defect in this ridge on an anterioposterior film picture. A fragment can often be seen because it is calcified or ossified. In old cases the fragments can be very large in size. Sometimes a lateral radiograph with the hock joint in as much flexion as possible is useful.

“A rather high percentage of loose bodies removed from hock joints contain bone. This is in contrast to OCD in other joints of the dog, where such ossicles are extremely rare. Surgery is the treatment of choice. With the leg in flexion, the loose bodies easily can be removed. Prognosis is good if surgery is performed early.”

A SIMILAR CONDITION

Stress fractures of the hock have been well known in racing Greyhounds for many years. However, these can and do occur very occasionally in other breeds. It is bittersweet irony that, in Shibas, it should have first been reported in a dog belonging to the author of the book on orthopedic disorders, namely me. The day after winning another Best In Show, my male suffered a very painful fracture in the hock as a result of jumping into a jumble of large rocks. See Fig. 6. “Track” Greyhounds avulse (tear off) a fragment of bone when they exert those tremendous and sudden tensile forces in racing. My Shiba did the same thing, apparently when bouncing out of a crevice between rocks while the hock was twisted. This severe trauma can be (and was, in this case) accompanied by the creation of a slight but significant subluxation between the talus and the several tarsal bones below it, adding to the pain. Surgery about a week after the injury was followed by hydrotherapy and restricted free exercise, and recovery was apparent, but occasional limping was still seen, thought at the time to be due to intermittent arthritis. Arthritis, consisting of swelling and usually some extra bony (“calcium”) deposits is a natural result of injury to a joint. However, when the limp returned a year later, further radiography revealed a previously-undetected avulsed fragment, and at the veterinary college this was removed and a plate affixed with pins. Since he had normal gait most of the time, I “brought him out” for a short series of shows, but following Murphy’s Law, he limped at those shows. After that, he was happily retired with his 8 international championships and lady-Shiba visitors, though he still thought we were going to a dog show whenever he saw his crate and my suitcase together!

Stress fractures (acquired, environmental) can be differentiated from genetic OCD mainly by the age of onset, the former occurring after full skeletal maturity has been reached and at an age when the dog is in top muscular condition. They are brought on suddenly, like a muscle strain or a bone broken in a fall. OCD of the hock occurs in young pups whose joints have bones that are still ossifying (turning to bone from cartilage and connective tissue) and thus in a very “plastic” form, easily distorted by less severe but constant stress. Minor subluxation may accompany stress fracture, while subluxation can range from minor to severe in congenital-developmental joint disorders. The OCD lesion is found on the top end of the talus, while the stress fracture avulsed piece is torn off the bottom. Stress fractures almost always show an obvious bone fragment on the X-ray picture, but more often than not, the OCD lesion is either all cartilage or hard to find on film, sometimes because bone has been partly or completely resorbed. The occurrence of stress fracture in the Shiba is probably very rare (mine is the only case I have in my files so far), while hereditary OCD of the hock is common enough so that an owner of a dog with rear-leg lameness should have this possibility checked by a team of radiologist and orthopedist, probably at a veterinary college.

DIFFERENT CONDITIONS

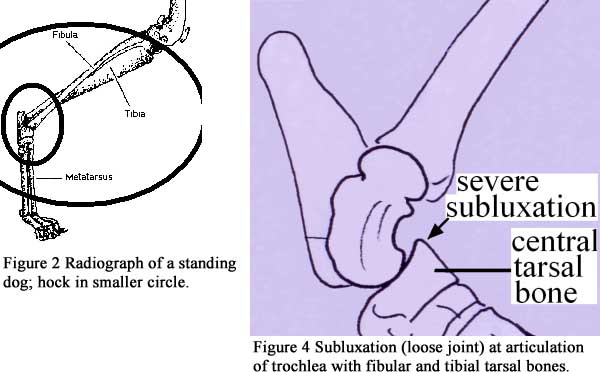

There is another, less serious, condition in the hock that poses no special problem in regard to veterinary bills and very little interference with leading a fairly normal life. It is commonly known as “slipped hocks,” but more accurately described as luxation (when completely out of alignment or position) or as subluxation (looseness, but retaining some positional relation, which is far more commonly found). Three of the illustrations accompanying this article are tracings from my own radiographs—two normal and one showing subluxation in the flexed position—and the other one is from the classic veterinary text by Miller, Christensen, and Evans. The condition shown in Figure 4 can evidence itself in a “double-jointed” or “super-extended” position. In the vernacular, “bending the joint backwards.” I have seen “slipped hocks” in Shar Peis, Chows, and a few Afghans, and feel sure that it exists in many others.

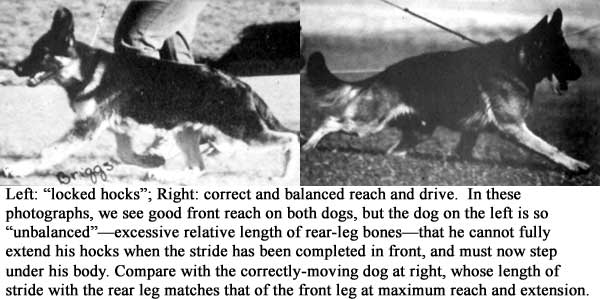

a postscript — Ever meet or hear of somebody described as “double-jointed”? His limbs (usually most obvious to you at the elbows or fingers) bend “backwards” beyond the normal range of joint extension. Some have even made a living of sorts as circus contortionists, in times past. This condition is seen in dogs, also. As a dog show judge for many years, I have had my hands on many a dog, and have watched other judges. One very experienced colleague in the conformation ring used to check the hocks of his favorite breed by grasping them (from behind) at the joints in such a way that the dog would not lift one leg to put the weight on the other. He then pushed forward to see if there was hyperextension or if the hocks refused to extend at all or normally. If the former, the dog had “slipped hocks”; if the latter, the dog had “locked hocks.” The locked-hock phenomenon is not very uncommon in German Shepherd Dogs of American bloodlines—the so-called “AKC type.”

Most modern AKC-type GSDs have been bred for an extremely exaggerated length of lower thigh and a placement of the metatarsus (when vertical) that is much further behind the pelvis than the founders of the breed specified. Since front-limb angulation cannot possibly match this exaggeration, and the last 40 or more years has seen “AKC GSDs” become almost totally lacking in front-limb angulation, such dogs often move with a high “goose-stepping” gait in front, and incomplete extension of the hock at the end of that rear limb’s extension, thus wasting time and effort in a breed whose claim to fame and utility once was its efficiency of movement, in addition to its character. (See other articles of mine on gait and structure.) I have also seen “locked hocks” in Afghan Hounds and other breeds. In some cases it is indeed an inability of the ligaments to allow full extension, and in others it is merely the result of an upright shoulder/upper-arm combined with overdone stifle angulation—the dog must waste time by lifting (“goose-stepping”) in front while the rear limb finishes its longer stride.