It is a thankless task! If, in a trial, a handler receives 100 points in protection, he has done an excellent job of training the dog. If, on the other hand, the score is 80 points, the trial helper was at fault Yet, in our more honest moments, we should admit that the sport could not succeed without the dedicated help of all the men and women who take time away from their dog training to become trial helpers

Unfortunately trial helper training has remained the stepchild of most clubs protection programs. Helper training, more often than not, is a faction of necessity: we have to have trial helpers for our trials, good or bad. So, the task of training a trial helper has most often been left to someone in the local club who might be a good or bad teacher. Often this is accompanied by the fact that there are few advanced dogs on which the helper can practice, or the club members don’ t want some rookie practicing on their Schutzhund 111 prospects.

All of this has retarded the development of good helpers in the numbers that the growing sport requires. Even in a local trial the helper may face dogs trained to the highest skill levels with physical qualities that vary dramatically At one time we mostly worked German Shepherds, and the occasional Doberman. Today, the trial helper may face a lightening-quick malinois and a strong, dominating Rottweiler in the same trial. Each demands a different and carefully honed skill that current helper training has provided on only rare occasions. The margin of safety is getting slimmer all the time and our need to provide the best possible test is becoming more challenging. Over the last several years we have seen dramatic changes in training theory, the trial rules and handling. For protection work to advance at the same pace we must expose our trial helpers to better theory and technique

Despite What a few showboating trial helpers may tell you, the good trial helper is much more the product of superior athletic ability than extended dog training experience. Certainly the helper must understand dogs and how they work, but it is more critical that he understand the physical requirements of the sport and how to meet these demands properly. Our best trial helpers have a whole inventory of physical techniques that ensure they will not work out of control or allow the dog to gain the advantage These are the same skills that any top athlete learns and develops on his way to the top

What this series doesn’t attempt to do is to tell you – the trial helper – how to work a dog. That would be pointless and foolish for no helper has the same physical skills as the others. To try to learn one method that applies for men and women, tall or short, fast or slow, would probably work, but create built-in limitations that would never allow anyone to reach maximum individual potential. Add to the equation the necessity of adjustments for working different types of dogs, from Malinois to Rottweiler’s, and it should be apparent that any one method just doesn’t fill the purpose

Instead, I would rather break down the helper’s work into individual skills and examine each to determine if there is some way to improve each helper’s technique. As with most athletic training, the greatest problem in development is first establishing foundation skills Only when the principles of good helper work are understood and conquered can the helper advance to developing the individual skills that distinguish each good helper from the rest

Helper work is a contest for power between man and dog. It is imperative that the helper understand that there is no vacuum in protection work: either the dog or the helper has the power. Often the helper attempts to solve this problem by trying to out muscle the dog with often disastrous results. Further, any indecision by the helper during the routine, even if only for a split second, gives the power to the dog where the helper needs to maintain control.

This doesn’t mean that the helper maintains power all through the routine, dedicated only to dominating the dog. If this would be the case only the strong would survive and then, not 100 percent of the time. There are those times especially during attacks where the skilled helper can use the dog’s power against the dog.

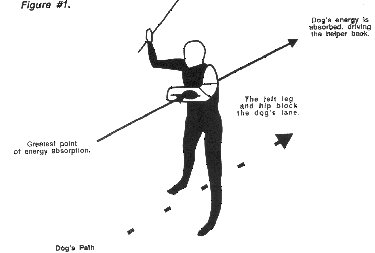

Most good helpers will tell you that the easiest dog to catch on an attack or courage test is the one that comes in the fastest and hardest. In these cases the helper actually uses the dog’s power to aid the trial helper in turning and starting the drive of the dog. The result of confronting the hard driving dog head on is demonstrated in Figure 1, where the helper is attempting to absorb the energy of the dog.

This approach is dangerous in that the helper’s whole torso and left leg is blocking the dog, not unlike the dog hitting a brick wall. The further problem is that the helper has nowhere to go: he is too busy absorbing the punishing power of the dog instead, he will first have to deal with the strike (usually by recovering from being driven backwards) and then have to start the drive from a dead stop, a task that is not easy with a 120 lb. Rottweiler.

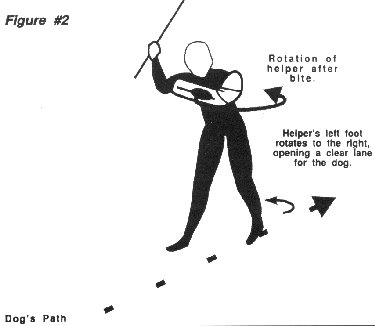

In Figure 2, the helper has opened up a lane on the sleeve side for the dog to travel through after the bite has been taken. Note that the path of the dog never changes from the moment before the bite through the beginning of the drive. What is a potentially dangerous situation suddenly becomes one where the dog’s full power is used by the helper to achieve a correct, safe and easier catch.

Therefore the good helper knows w hen to let the dog have the power and when to take it from him.

Over the past decade all popular sports have

been affected by the field of bio-mechanics, the study of how body

structure works under different physical demands.  While

we in the more economically deprived sport of Schutzhund don t

have the luxury of high speed computers and sports medicine

specialists there is still a great deal to be learned from simple

observation. There are few sports endeavors that so strongly test

the athlete for strength, quickness, and speed as does trial

helper work.

While

we in the more economically deprived sport of Schutzhund don t

have the luxury of high speed computers and sports medicine

specialists there is still a great deal to be learned from simple

observation. There are few sports endeavors that so strongly test

the athlete for strength, quickness, and speed as does trial

helper work.

It requires many of the same physical characteristics as a good boxer, amateur wrestler, or weight lifter, but also includes the need for speed. The reason this fact is so often overlooked is that helpers are never rated with a score or allowed to come in first place: the well-trained dog always wins and the good helper always loses in the test of Schutzhund. The only sense of winning allowed to the helper is in knowing he worked the dog safely and with a strong fair test. many of us can recall the winners of many national championships but can’t recall the helpers who worked those championships?

In studying structural movement I would like the helper to keep in mind two principal concepts, both of which will ensure a good foundation for the work. The first is to always maintain platform. The second is to always use leverage in the strength portions of the exercises.

For those who ski, surf or engage in the martial arts the platform is not a new concept. The idea is to try to keep the body as vertical as possible, from the feet through the shoulders, all through the work. The platform doesn’t concern just good balance but also the ability to use the maximum amount of power available when other forces are pulling against the athlete.

(Think of many of the helpers you) see

in trials. The legs are stiff and extended. The upper body is

significantly out of vertical, tending  to

lean in the direction of the dog is pulling on the sleeve. During

the drive this decoy is attempting to maintain speed by

taking long strides, which seems logical. The problem arises from

the fact that as the length of the stride increases the feet are

no longer under the helper and he becomes less vertical and more

unstable.

to

lean in the direction of the dog is pulling on the sleeve. During

the drive this decoy is attempting to maintain speed by

taking long strides, which seems logical. The problem arises from

the fact that as the length of the stride increases the feet are

no longer under the helper and he becomes less vertical and more

unstable.

Watch trial helpers and you will often see that the beginning of the drive works well but as the helper gains speed and the stride lengthens he has more problems driving and controlling the dog. If, instead, the helper can keep both feet under him he is able to counter the dog’s pulling by driving physically up with his knees. The knees then become both pistons and shock absorbers. Speed is created not by a longer stride but in a short stride with increased foot speed. The combination of a shorter stride and bent knees gives vertical strength and the ability to counter against the dog’s pulling during the drive by the helper pulling straight back and driving up with the knees.

The second concept of leverage is using body position and large muscle groups to gain the advantage over the dog.(The bent-forward) helper, because of his out-of-vertical position must use his lower back muscles to work against the dog. While his strength is aided somewhat by the biceps on the sleeve arm the helper is allowing the dog to leverage him more than the other way around. When the dog pulls on the sleeve during the drive the lower back is the only large muscle group that is keeping the helper from falling.

How much more advantage a helper can have if he can bring in the upper back, shoulder and leg muscles. Future installments on the trial escape and drive will demonstrate these techniques. Another important reason for keeping the lower back out of the work involves injury. I know of few older trial helpers that don t suffer from bad lower backs and part of this comes from the failure to maintain the platform in their earlier years.

Leverage is also aided when the helper makes the dog bite certain portions of the sleeve rather than others.If a dog is allowed to bite the end of the sleeve at anytime during protection, the dog gains leverage by swinging the helper around from the end of the helper’s arm. If, on the other hand, the helper can precisely make the dog bite near the elbow, the helper will gain the use of both the biceps and shoulder to leverage the dog into proper position This is not as difficult as it sounds, for during the time just before the bite the helper can aim the bite bar and force the dog into the approximate position of the arm that is most advantageous for the helper.

Armed with only the platform and a concept of how to achieve maximum leverage, the trial helper can draw from a broad spectrum of techniques for each individual exercise that ensure success and confidence. In the next installment I will examine the bite and show how it is the first step to helper success.